3. Propaganda and Special Interest Groups

Section author: Andrea Bruno <bruno.andrea.191@gmail.com>

How often have you looked at advertisements and glimpsed the hand of the author or the wallet of the sponsor which created it? This is a skill we are going to practice here. First, I would like to introduce you to the concept of a special interest group. A special interest group is an organization which represents the political interests of its members. Such members are often unified under a common industry, political orientation, religious identity, or social class. An example of an industry group is the National Milk Producers Federation (NMPF), which represents dairy farmers. Members of NMPF pay a recurring fee to the organization and are given information about lobbying efforts and the ability to influence policy pushes in exchange.

Some famous special interest groups include the:

National Rifle Association

American Israel Public Affairs Committee

Planned Parenthood Action Fund

American Association of Retired Persons

National Association for the Advancement of Colored People

You will notice that special interest groups represent a broad variety of issues and demographics. When people complain about interest groups and lobbyists in government, they are usually implying a problem with corporate corruption. However, if you want to stand up to malicious influence, it is important to be specific and knowledgeable about the political actors at play.

So let’s talk about some of them.

3.1. The National Association of Manufacturers

The National Association of Manufacturers (NAM), was founded in 1895 to represent American industrial firms after a recession in 1893 shook the economy [Steigerwalt Jr, 1952]. During this time, they were primarily concerned with lobbying on behalf of export missions which would bolster demand. (They were even responsible for the United States’ mission to build the Panama Canal for greater port access, which involved an American-backed revolution in Panama! This project cost 193.1 billion dollars in today’s money!) [Maurer and Yu, 2006]

However, everything changed when the great depression (1929-1939) seized the global economy.

In response to the hardship, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, serving between 1933 and 1945, implemented his new deal policies, which aimed to rebuild the economy with a progressive agenda. This was a threat to NAM because the new deal strengthened labor unions and allowed workers to demand higher wages and better working conditions [Rudolph, 1950]. Unfortunately for NAM, Roosevelt’s administration ignored their efforts to influence policy. However, where NAM failed, another interest group, the American Liberty League, would succeed.

3.2. The American Liberty League

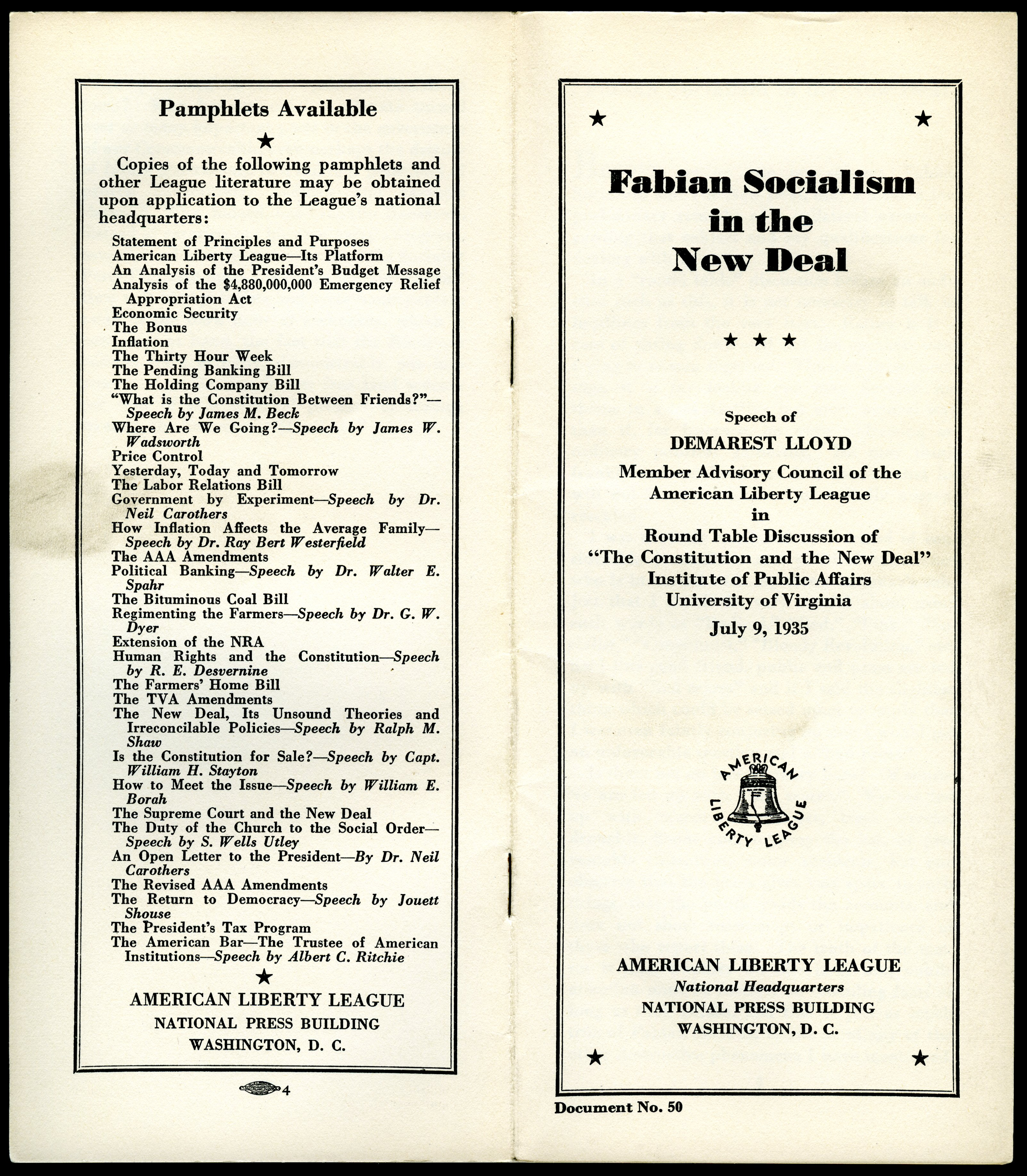

The American Liberty League formed in 1934, and was funded by the DuPont family and another handful of business elites [Rudolph, 1950].

The league was founded in order to fight the new deal, and in pursuit of that mission, they executed a large scale propaganda campaign.

They hired Edward Bernays, an early pioneer of public relations who wrote the book Propaganda in 1928.

Under Bernays’ consultation, the League mailed “education” pamphlets to schools, news papers, and churches, where they were absorbed by the public with one clear message: support business, stand against the new deal.

Figure 3.2.1 Jouett Shouse Collection of American Liberty League Pamphlets.

3.3. The Return of NAM

NAM (The National Association of Manufacturers – remember them?) learned from the methods of the American Liberty League, and employed a new strategy. Instead of trying to approach congress with their agenda directly, they decided to target the public with pro-business media meant to dampen criticism of industry [Oreskes and Conway, 2023].

In 1940, they released the film you can click on here: Your Town (1940)

I want you all to take a moment to think about what NAM would have gained from this movie. Do you feel it is effective? Why and why not? If it is, how so?

Once you’ve given it some thought, we’re going to pivot to another special interest group: The Global Climate Coalition, also known as the GCC.

3.4. The Global Climate Coalition

Before we delve into this group, I want you to guess what the goals of the GCC might have been. Take a look at their logo and pay attention to what they are trying to evoke:

Figure 3.4.1 The logo of the Global Climate Coalition.

Now, whatever you may have assumed, (perhaps that this is an environmentalist group, that their mission is to preserve the world’s ecosystems and perform activism on behalf of the planet, etc…) they made you think this intentionally.

But they have tricked you. And so did I! The GCC is actually a shell nonprofit which operated out of the headquarters of NAM. It is NAM’s twin with a green face!

According to John J. Berger in Climate Myths: The Campaign Against Climate Science [Berger, 2013],

“...The Global Climate Coalition (GCC) [was] set up in 1989 by the

public relations firm of Burson-Marsteller for the fossil fuel

industry and its industry allies.

Meeting at the offices of the National Association of

Manufacturers, this influential coalition was the apparent hub of

the fossil fuel industry’s climate campaign for years.

From 1994 at least through 1998, the GCC spent upwards of $1

million a year to promote its climate views.”

So, what do we think those ‘climate views’ might have entailed?

Well, they spent over 8.3 million dollars funding an advertising campaign profligating climate denial.

And, according to internal documents, the GCC’s sole stated purpose was to prevent any mandates which would reduce carbon emissions.

One of their strategies was to wield economics to imply that any government intervention would be devastating to the financial bearings of ordinary Americans.

If you look back at NAM and the ALL’s strategies in the early 20th century, this playbook will be familiar.

As Berger states, “This utilization of economics based on the exaggeration of costs and minimization of benefits became a key component of the GCC’s strategy to oppose climate action.”

Of course, they aren’t interested in a balanced cost-benefit analysis of the short-term transitional expense to the energy sector as firms respond to new regulations vs. the continued cost of entire cities, crops, and human lives lost to climate change. And indeed, the economic impact of natural disasters is far more destabilizing than that of regulation. According to a study done by Maximilian Kotz and Anders Levermann, the economic loss associated with climate disaster outweighs the cost of adaptation by a factor of six, with the cost of climate change by 2025 being estimated at ten trillion dollars in today’s money.

However, beyond their financial argument, the GCC would also testify about the state of climate researc before congress, arguing that the science was inconclusive, despite the overwhelming consensus among experts.

And they didn’t just play this game in the USA. During the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development in 1992, an event which attracted representatives from 172 countries, the GCC presented the following documentary:

Now, before we continue, I realize I have been exposing you to a steady stream of bogus, harmful, but disturbingly effective propaganda. So I would like to remind everyone that this documentary is, indeed, a lie.

The GCC does not want you to think about the greenhouse effect.

It does not want you to think about coastal communities drowned by glacial water, it does not want you to think about the ravaging impact of worsened flood and drought seasons on crop health.

You are not meant to think about the wildfires or the acidic ocean or the possibility of mass-extinction.

But please do think about it.

And, as we recognize the dishonesty here, is important to understand the consequences of the GCC’s campaign.

The Bush administration cited the GCC as a driving influence in their decision to leave the Kyoto-protocol in 2001, which was an international treaty meant to mitigate the release of greenhouse gasses [Farley, 1997].

But surely this is as culturally impactful as oil propaganda has gotten, right? That sure would be nice, wouldn’t it?

3.5. Green-washing and Recycling

One thing you should absorb from this tutorial is that propaganda disguises the motivations of its propagators. It is insidious, and it’s not easy to recognize. When teachers cover basic lessons on propaganda, they often refer to old-time war posters featuring Uncle Sam pointing at the viewer, trying to elicit feelings of patriotism to drive up army enlistments. However, this is not the most dangerous form of propaganda, because Uncle Sam is at least telling you what he wants. Indeed, some of the most impactful propaganda our lifetimes did not state its mission aloud, but instead aimed to disguise and misdirect.

You might have even internalized it.

Let’s take a look at one example:

Recycling.

Before we begin, let’s watch an old ad which may be nostalgic to some of you. During the 80s, 90s, and early 2000s, such PSAs dominated the airwaves:

https://digital.hagley.org/VID_1995300_B01_ID02 (Sourced through Larua Sullivan, NPR. 2020)

At least this piece is generous enough to inform you that it was funded by Dupont Chemicals. This gives you a good hint at what it’s going for.

However, most recycling campaigns are not nearly so overt.

But before we go further, I’m sure many of you are raising your eyebrows at the screen. After all, why is it a bad thing that oil companies are encouraging people to recycle? Recycling is sustainable, isn’t it?

If this is what is going through your mind right now, I’m afraid I have some unfortunate news.

Less than 10% of plastic waste has ever been recycled.

Most types of plastic are not recyclable at all. Only plastic with resin codes 1, 2, and 4, (out of 7) are even viable for recycling. Plastic also degrades with every turnover, so it can’t be recycled more than once.

Despite this, plastic manufacturers designed resin labels to imitate the recycling symbol, making the public believe all plastic could be recycled.

China used to buy plastic recycling from the US for manufacturing projects, but they stopped purchasing it in 2018. Even firms which successfully sort viable recycling material find it impossible to sell. This is because…

Recycling is costly! It is significantly more expensive to recycle a plastic bottle than it is to make a new one [United States Environmental Protection Agency, 2024].

So, for the reasons listed, plastic recycling is not a solution to the problem of plastic waste. Now, why might oil companies have wanted you to believe that it was?

NPR interviewed a man behind the early recycling campaign during the 1970s in their piece How Big Oil Misled The Public Into Believing Plastic Would Be Recycled, and this is what he had to say to them:

"If the public thinks that recycling is working, then they are not

going to be as concerned about the environment."

Oil companies were even responsible for putting blue bins on everyone’s curb. And, if you have ever seen a bench made out of plastic recycilng? They put that there too. (Which cost a lot, mind you!)

So, to summarize, In the 1970s, the public was getting worried about the growing issue of plastic waste. In response, big plastic invented the recycling movement in order to make their products seem safer than they are, and to make the public feel empowered in the solution. But what does this look like today?

If you’re wondering who might be funding this non-profit, look no further than their list of contributors, which includes Exxon Mobile, Chevron, Dow, and DuPont.

To bluntly summarize the recycling dilemma:

Takeaway: when you view something which is meant to be informative, ask yourself,: was this made by a scientist or a marketing firm? If it was made by a marketing firm, who paid for it? What do they want you to believe? And why?

If it was made by a scientist, what do their peers think? As we will learn soon, you shouldn’t trust someone just because of their title.

3.6. Works Cited

See also the bibliography.

Berger, John J. Climate Myths: The Campaign against Climate Science. Northbrae Books, 2013.

Kotz, M., Levermann, A. & Wenz, L. The economic commitment of climate change. Nature 628, 551–557 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-07219-0

Farley, Maggie. “Showdown at Global Warming Summit.” Latimes, 7 Dec. 1997, web.archive.org/web/20160118234039/http://articles.latimes.com/1997/dec/07/news/mn-61743/2.

“The GCC’s Position on the Climate Change Issue.” Global Climate Coalition Mission Statement, web.archive.org/web/20000815060228/http://www.globalclimate.org/mission.html

“Global Climate Coalition.” DeSmog, 30 June 2021, www.desmog.com/global-climate-coalition/.

MAURER, NOEL, and CARLOS YU. “What T. R. took: The economic impact of the Panama Canal, 1903–1937.” The Journal of Economic History, vol. 68, no. 3, 2008, pp. 686–721, https://doi.org/10.1017/s0022050708000612.

“National Association of Manufacturers.” SourceWatch, www.sourcewatch.org/index.php/National_Association_of_Manufacturers. Accessed 16 Dec. 2023.

Oreskes, Naomi, and Erik M. Conway. The Big Myth: How American Business Taught Us to Loathe Government and Love the Free Market. Bloomsbury Publishing, 2023.

Rudolph, Frederick. “The American Liberty League, 1934-1940.” The American Historical Review, vol. 56, no. 1, 1950, p. 19, https://doi.org/10.2307/1840619.

Steigerwalt, Albert K. The National Association of Manufacturers: Organization and Policies, 1895-1914. University of Michigan, 1952.

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). 2024.