2. Overall principles

2.1. The constant mantra: automation

I have my students repeat my mantra constantly (until they are probably sick of me):

The purpose of computers is to automate repetitive tasks.

That is what this book is all about.

2.2. When should you automate?

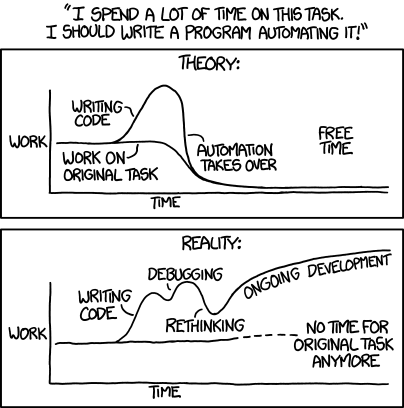

By being alert to where your time goes, you will eventually develop your own instinct for when you should automate a repetitive task. There is an xkcd vignette that illustrates how this is subtle:

Figure 2.2.1 The xkcd mouse-over for this vignette is: Automating comes from the roots “auto-” meaning “self-”, and “mating”, meaning “########”.

In Section 5.4 I will give some examples of situations in which I show how to automate tasks with a script that would be tedious to carry out individually. Working through them will give you some examples to start from, as well as a feeling for how much time you save by automating.

2.3. Mixing user-level and programming

You should always be ready to write a program. You should be able to drop in to your editor casually, without feeling “Oh no, I have to do this now…”. Then you write a shell script or python program or C program to do a repetitive task.

You might only have one or two simple programming paradigms (like a shell script that does a simple for loop over a wildcard of files in the current directory), but you should have that.

[…]

2.4. Customizing your environment

2.4.1. Motivation

But Jake expected efficiency as well as proficiency from his staffers.

“The biggest part is key bindings” – keyboard command shortcuts – he told her. “You work most effectively when your fingers never leave the keyboard. Learn the quickest way to accomplish your most routine tasks, and you will find that you are enormously more productive.”

What followed was the beginning of Alien’s transformation as a programmer. […]

“These skills will serve you for a lifetime,” Jake continued. Instead of a series of almost haphazard, improvised steps, Alien would need to break all of her tasks down into a careful sequence. Internalize this process and it would become automatic and nearly effortless, like a race car driver shifting gears, or a soldier assembling a rifle.

—Jeremy Smith ‘breaking/_and/entering| the extraordinary story of a hacker called “alien”’

2.4.2. Graphical

First you should be aware of what the X Window System is, how it is network transparent, and how its pillars (the X server, Xlib, the X application programs, the window manager) work together.

Then you should understand how modern integrated desktops fit into the X Window System picture.

There are many different graphical setups used by experienced hackers. Some take the default offered by a desktop environment and do little with it, while others customize it into their own beast.

Everyone should explore virtual desktops. These came along as a novelty in the 1990s and have become crucial tools for being more productive. Your window manager or desktop environment probably allows you to configure that.

You should also learn how to set up key bindings, window focus options, and other properties of your window manager.

Which desktops exist? There are so many that I would not be able to list them all. I will briefly mention gnome3, kde, mate, cinnamon, xfce, and the no desktop option.

The gnome3 desktop imposes a specific model based on the idea that you should have one GUI program with focus, with most of your attention on that. It also has a particular model for virtual desktops.

Your relationship to your graphical environment is discussed in greater depth in Section 7.

2.4.3. Shell

You should customize your shell. This is your greatest productivity enhancer and it is where you will spend most of your time combining different programs to work together. This is discussed in more detail in Section 5

2.4.4. Sysadmin

System administration is a whole separate topic, discussed in other

places (I have a few chapters written of a Sysadmin Hacks book),

but I will say a few words here.

You should know your computer and its operating system intimately. You should have a basic understanding of how operating systems work, how it manages processes and memory and disk. Some discussion of memory probing is in Section 9

You should know how to encrypt a filesystem and how to make backups.

You should know your network, at least the subnet at your house or office and who it is who routes you to the network at large. As a hacker who is not a professional sysadmin you can stick to simple networks and you don’t need to know the intricacies of networking a whole company.

2.5. The hacker and the sysadmin

Should a hacker also be a sysadmin?

2.6. A collection of tips from experienced hackers

These quotes are collected from some top professionals I know who gave a quick off-the-cuff answer.

Christopher Gabriel, hacker and free software entrepreneour

“‘automate as much as possible’ and ‘track everything with version control’ are good generic tips

Charles Ofria, computer scientist

To become a power user, I think it’s important to understand Unix history and philosophy - it just clears up WHY commands are structured the way they are, why some odd sounding names make sense, etc. This goes along with automate, but it’s also critical to know how to customize your own shell experience to facilitate how YOU work: shell scripts, aliases, dealing with paths, etc.

Alan Batie, sysadmin

perl or python will be your friend

Nelson Minar, hacker and web development pioneer

perl is your enemy

Alan Batie

use perl in strict mode with warnings

Nelson Minar, hacker and web development pioneer

Learning how to learn. Man pages, of course. But also https://tldr.sh/ and Stack Overflow.

Laura Fortunato, anthropologist

You need to know how to touch type.

“Not a real robot” @baconandcoconut

Don’t worry if you can’t memorize everything. Many of us look stuff up over and over again, or keep a personal list of useful, infrequently needed commands.